Throughout the years and even now, I have often been asked the view Shinto holds in regard to LGBT+ people and culture. As someone who is both nonbinary feminine and pansexual, with most of my loved ones being apart of the LGBT+ community, and some who practice Shinto as well, this is a topic that is very close to home and personal for me. I wanted to write about this for a very long time, and talk about this in my last article about Shinto and sexuality, as they are related. However as this is such an important topic to me, I felt it deserved it’s own article. There are so many things I want to express in regard to this topic so this won’t be the only article about it!

Historically speaking in Japan, there are many examples of LGBT+ people and practices that were present, a prominent and most-cited example being that it was commonplace and even a part of samurai culture to be in gay relationships. It wasn’t until the Meiji era in 1868, and the influence of Western culture, that it began to be viewed as uncivilized and wrong. As a result, a stigma began to rear it’s ugly head, and many important LGBT+ rights began to be lost. Under pressure, openly gay and lesbian relationships; writings and art of them too – began to disappear. Trans and gender nonconforming people began to be pressured to conform to their assigned gender at birth, instead of being able to be who they are freely. In addition, stricter gender roles and heavier patriarchal ideals were enforced even further. While it wasn’t absolutely perfect or progressive and there were still plenty of issues, with the advent of the Meiji reformations, any sort of openness and potentiality for progression was completely shattered.

However, much time has passed since 1868, and in the current era in Japan, thanks to the enduring influence of the past despite the Meiji reformations, and the present influences of Buddhism, and especially Shinto itself – the hostility towards LGBT+ people is not as severe when comparing with other countries. Despite the old Western influence remaining in that we still lack full legal equality in Japan, progressions and reforms are happening fast and in great number, despite the current political party’s objections – and for that I am very grateful.

Thankfully, there are lots of excellent resources about the LGBT+ history as well as the present situation in Japan and Japanese culture in English, in published books and online – so I won’t get too far into it for this article since I want to focus on the Shinto side in particular which isn’t as often talked about.

The answer to the question on everyone’s mind of this topic – “What is Shinto’s view on LGBT+ people?” isn’t an easy answer. Shinto is the farthest thing from a monolith. There is no dogma, and no unified organizational structure overseeing all of Shinto in itself. Jinja Honcho comes close to a sort of unifying organizational force, but there are still the 12 government registered sects of Shinto, hundreds of individual shrine faiths that while not officially registered as sects, are essentially as such in that they don’t align with Jinja Shinto’s common views – such as the focus on Amaterasu Omikami – for example. Shinto also encompasses the thousands of varied folk practices in rural areas; and holds a very long and complicated history.

In other words, to put it simply, there is no true existence of an authority to speak for all of Shinto in and of itself as a whole practice. There are authorities in each tradition, such as the Head Shrines where the faith and worship of a kami began, that maintain the general beliefs, history, myths, stories, and rituals. But as Shinto in it’s very essence is not dogmatic – every tradition, shrine, and each individual priest can and will have differing views and opinions about the various different aspects. It can even be as split down to two priests working at the same shrine having completely different interpretations on beliefs.

While Shinto is a practice that has a lot of freedom in interpretation and encouraging individual thinking, I strongly feel, personally speaking, this is not a “free card” excuse to dishonor the core values that makes Shinto, well, Shinto – the Way of Kami. Respecting and honoring nature, supporting each other, caring for each other, respect to our ancestors, working to be good people, taking care of the community, and so forth. This is the common thread that unites all of Shinto – the different traditions, the shrines, and the practices.

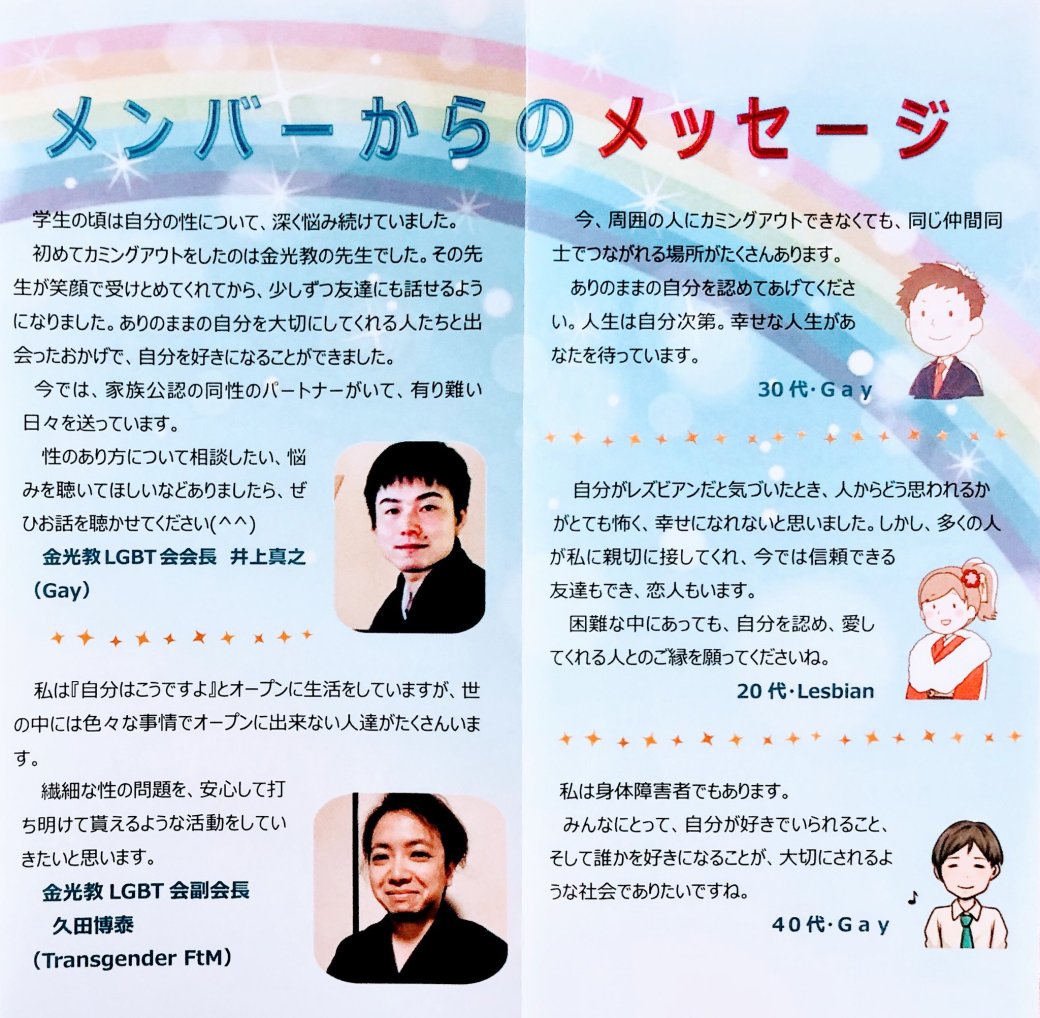

That being said, while there isn’t a simple and direct answer to Shinto’s view on LGBT+ people as a whole – I can say one tradition at the moment has made a groundbreaking announcement on matters for the LGBT+ community. This year the Head Shrine of the tradition I follow, Konkokyo Shinto, openly, officially announced and confirmed support of the LGBT+ community. This makes it the first Shinto tradition to do so. The Head shrine is also supporting the Konkokyo LGBT Kai (Group), run by LGBT+ clergy, with other clergy and laypeople members who work to support the activities of our group – myself and my partner included.

Many of our Konkokyo shrines had been holding same-sex marriages for many years, but with this decision, we now are also actively supporting the community as a whole, with our shrines being safe spaces for LGBT+ folks. Having the official approval from the Head Shrine is so validating and I feel so proud and happy to be a priestess of Tenchi Kane no Kami and of Konkokyo. I wrote a full article about the announcement here: http://witchesandpagans.com/pagan-paths-blogs/living-with-kami/konkokyo-lgbt-kai.html

I can only hope other traditions follow suit, and have their support be clearly defined.

Informational pamphlet from the Konkokyo LGBT Kai, about clergy and laypeople, as well as terminology

While there may not be an official support from Jinja Honcho, other Head Shrines, or traditions (yet!). I still know of there being a lot of openness and acceptance. For example, Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America has also been holding same-sex marriages for over 20 years, and welcoming of LGBT+ parishioners and worshipers. In Japan, many other shrines have been holding marriage ceremonies for same-sex coupes too. Within the Jinja Shinto sphere, I know an ordained priestess who is a trans woman, and openly bi and gay priests too. Generally speaking in the Shinto community as a whole, it is very open and accepting. I have only encountered a few people who have not been accepting, but thankfully they are not the majority.

This makes sense as well, as historically Shinto has generally had LGBT+ friendly views – being LGBT+ was not seen as tsumi, or a “wrong deed that went against nature – a crime”. There are records of ancient miko of the Izu Islands, who were said to be “men who lived and thought of themselves as women”, but it was very clear in the ancient era only women had the power to be miko – female mediums, spiritworkers, and priestesses in the ancient era – so the miko of the Izu Islands were truthfully trans women. There are other examples of miko not from the islands who fell in the same definition in ancient times. In addition, even some of the nature-spirit and ancestral kami themselves were viewed and are still viewed as being gay. For example, an excerpt from “Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan” by Gary Leupp writes,

“During the Tokugawa period, some of the Shinto gods, especially Hachiman, Myoshin, Shinmei and Tenjin, “came to be seen as guardian deities of nanshoku” (male–male love). Tokugawa-era writer Ihara Saikaku joked that since there are no women for the first three generations in the genealogy of the gods found in the Nihon Shoki, the gods must have enjoyed homosexual relationships”

In addition, one could understand quite a few nature-spirit kami as transgender, genderfluid, nonbinary, and agender too. For example, the first three kami, Ame no Minakanushi no Kami, Takamimusubi no Kami, and Kamimusubi no Kami could be interpreted as agender, as they are said to be genderless in their myth. The next example would be Tenchi Kane no Kami, who is said to be a kami who is encompassing of all genders, but also genderless too. One could interpret them as nonbinary or genderfluid.

Then we have Amaterasu Omikami herself as well. In one myth, she dressed in masculine warrior clothing and hairstyle when she confronted her brother, Susanoo no Mikoto. One could interpret this in many ways in regard to how she expresses her gender as a kami that is not always fully feminine. In addition with regard to her sexuality, depending on one’s interpretation of the cave myth and Ame no Uzume no Mikoto’s exposure of her breasts, one could see her as having either lesbian, bisexual, or pansexual attraction. This interpretation can be further supported in the ancient practices of the miko priestesses of Amaterasu Omikami. In some of these practices, the priestesses would ritually be wed to Amaterasu Omikami, and also share of an intimate bond with her in sacred ceremonies.

This practice was not only limited to Amaterasu Omikami, but many other female kami as well, such as Ame no Uzume no Mikoto herself, and Konohanasakuya Hime no Mikoto. Since both Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and Konohanasakuya Hime no Mikoto also have husbands, Sarutahiko Okami and Ninigi no Mikoto respectively, this also can be interpreted in a lot of different ways that is not particularly heteronormative.

Inari Okami is one of the most prominent examples, and often seen as a LGBT+ icon – sometimes they are a man, sometimes they are a beautiful woman, and sometimes they are androgynous, sometimes they are no gender at all, and sometimes they encompass many or all genders. One can interpret this as Inari Okami being known as a shapeshifter, or some may see Inari Okami being multiple kami as one – I feel the interpretation of Inari Okami as genderfluid, or nonbinary, or any other expression, is also just as valid.

People may not agree with these interpretations or even see the concept of kami having gender like people is incorrect, or foolish to believe. However, if the kami mythologicaly and traditionally are said to have genders, have sex, attractions, and marriage – I believe it is not out of place as an interpretation. Someone personally seeing some kami as a part of the LGBT+ community for their own personal belief harms no one. On the contrary, it can help to develop a deeper bond, trust, and understanding between us and the kami. Which that sincerity is key and most important.

Now, I say this in regard to nature-spirit kami in particular, but in Shinto, once-living humans are also worshiped and respected as ancestral kami, often referred to as “mitama-no-kami”. Someone who is a part of the LGBT+ community and has passed away is worshiped and enshrined as a mitama-no-kami just the same as anyone else, and to be properly respectful, they would still be honored as who they were when they still had a physical body – that does not change.

In addition, as I mentioned earlier, samurai had various romantic gay relationships. They too are enshrined as mitama no kami. One may know famously about Oda Nobunaga, who is enshrined as a mitama no kami, and Ranmaru’s romantic relationship. As well, there is one such famous example of a mitama no kami who was most likely a trans man – Uesugi Kenshin. Many have said he could have been a woman in disguise – but – he had various medical checks and observations of his body by professionals at the time, and was still referred to as a man and could act as leader of the Uesugi clan without falter.

It is even recorded he experienced illnesses pertaining to his abdominal area every month around the same time of the week, but this did not change any existing records in regard to his gender. It is also extremely odd that for a daimyo (samurai warlord) at that era, where it was common to have multiple concubines to secure a successor, he did not have any biological children and even faced a succession crisis that led to adoption. Of course, there is no way we can confirm historically of whether he was a woman in disguise or a trans man, but there is a lot of evidence historically pointing to him being trans. He is now enshrined as a mitama no kami at Uesugi Jinja in Yamagata Prefecture.

While there is still so much I want to talk about on this topic, and I could most likely write a book! I want to mention something perhaps not directly related as much but a fun mention: the rainbow’s colours are sacred in Shinto, as seen in the 5 sacred colours used for many different sacred items in Shinto. Red, Yellow, Green, White, Violet. The colours are said to represent the 4 directions around the world, and our own soul.

I hope then, that in all 4 directions around the world, people can come to realize that LGBT+ rights are also human rights, and we aren’t odd, strange, nor dangerous. We are all apart of nature, all apart of this universe together. Let’s respect the various colours of everyone’s own souls, and work to uphold and support each other as a whole, unified community with love.