With the recent ban on adult content on Tumblr, it has given way to a lot of discussion about adult content online and what is or isn’t acceptable. Legitimate issues were brought up in how violence is more normalized than intimacy and sexuality, and how the bans would affect sex workers and nsfw artists greatly – Tumblr, one of the last safe mainstream social media platforms that could ensure an income and audience base is now also being ripped out from under them. I feel this is not right and even a dangerous and irresponsible decision to make. Instead of relying on bots and algorithms to moderate between adult content and all-ages content, they should hire a dedicated moderation team, and proper safety features into the site to protect minors, but also while not censoring adult content creators and their adult consumers. There were ways that worked before that do not require a site-wide ban.

Unfortunately, this issue branches from a much larger issue of bans across the internet based on how society views these topics. In many modern societies today, and even in the past, sexuality is often viewed as something very taboo or forbidden. It is something only for the minds of adults, and even then, only married adults in a strict setting with only certain positions being “acceptable”. In this, there is a high sense of rigidity, shame, and hiding in sexuality.

I do not agree with this and feel this viewpoint is very wrong. Nudity and sexuality itself should not be viewed as shameful or wrong, because there is nothing inherently wrong about them. We are all born naked, and the action of sex itself is what creates life. Why can we show and talk about gory murders in detail with a degree of normalcy, but when there is a non-explicit sex scene, it is somehow more scandalous, forbidden, and dirty? I feel strongly instead it should be something understood as beautiful, and definitely should not be seen as a taboo action, especially comparing to a gruesome murder.

Learning about sexuality, and being comfortable about nudity is something I feel should be more open to explore for people of all ages, and work to remove the stigma surrounding sex and nudity.

That being said, I do strongly feel minors should be protected from eroticism, that is, something inherently intended to be erotic and presented in an erotic nature. I feel that eroticism is a more advanced area of sexuality that should be kept in adult spheres only and explored by adults only. It’s important to let kids be kids and understand about their sexuality in a healthy and educational way, but leave erotic content for 18 and older. That isn’t to say eroticism is what is taboo, wrong, dirty and should be hidden, but should be explored in an open, healthy, and safe way only once someone matures into an adult.

In relation to that, on the topic of showing a “female-presenting nipple” as Tumblr called it in their guidelines, such as a topless woman just lounging as a topless man would in a non-erotic way, or a breastfeeding woman, is not erotic nor should be seen as such. I personally feel non-erotic nudity and sexual educational content should not be censored at all, and erotic content can be accessed by adults-only without banning it entirely. The fact there is no understanding between these differences in content, nor any care to understand between them, and just labeling anything relating to sexuality as wrong, dirty, taboo, and forbidden to be banned – leads to many issues and shame surrounding our bodies and our understanding of sex, sexual attraction, and sexual desire.

This is such a harmful and unhealthy view in our society that is being enforced by this censorship online, and in addition has very real detriments to people’s livelihood. It affects sex workers, and erotic nsfw (not safe for work) artists livelihood and ability to survive; and removes access to a safe community. In extreme cases, it is pushing sex workers into dangerous communities where their lives can be at danger either by trafficking or murder. Censorship, banning, lack of education, and hiding these topics away also leads to other broader issues that harm people greatly. Such as sexual abuse, transmission of STI’s (Sexually Transmitted Infections), unexpected pregnancies, body image issues, self-esteem issues, and more. I feel strongly we must work toward being more open to educate about sex, sexuality, and our nude bodies with no shame. And for the adult sphere, adults also need to understand exploring eroticism, and erotic content in itself, is not taboo, shameful, or wrong. Understanding that those who are sex workers or nsfw artists are not inherently deviant perverts or bad people – after all, there are plenty of clients who request their services. This isn’t something wrong or dirty. It’s a part of the human experience, and again, nothing is inherently wrong, bad, or evil about it.

This is a large part of why I practice and why I love Konkokyo Shinto – sex and our bodies is not seen as something wrong, bad, or shameful. It’s a part of nature, it is an action that is one way to bring pleasure, to express love deeply, as well as the action that creates life itself. It is something that brings love, pleasure, joy, and life. Exploring our own bodies and sexuality consensually with others helps us to understand ourselves better and helps us to learn to love and treat ourselves and each other well. Within Shinto as a whole, this is expressed in various myths and other shrine traditions too.

I’ll start from one of the oldest myths, the first and most direct example of this belief and view – the creation of the islands of Japan, and the myriads of kami which populate the world. The traditional myth goes that after the first generations of kami were born from the divine universe’s energy, the last generation born this way was Izanagi Okami and Izanami Okami, who were also the very first kami who got married.

A famous line in this myth is when Izanagi Okami points out he has something “extra” but Izanami Okami has something “less”, so he suggests something good may happen if the extra part he had would compliment the part she did not have. And thus, the two kami are said to have discovered sex.

Because of this discovery, the two kami were able to create many children, which were both the islands of Japan, and the millions of kami that inhabit the islands. In this sense, sex is viewed in an extremely respected and positive light. Without that action, nothing would exist. And indeed, even for us as humans, without the action of sex, we could never continue on in our survival as a species. It is viewed as a highly sacred, but also very natural and beautiful action. There are even sacred Kagura dances that recreate this event via an implied (not erotic or explicit, as it is a public dance where minors also attend) way between Izanagi Okami and Izanami Okami, and it is not seen as wrong or perverted.

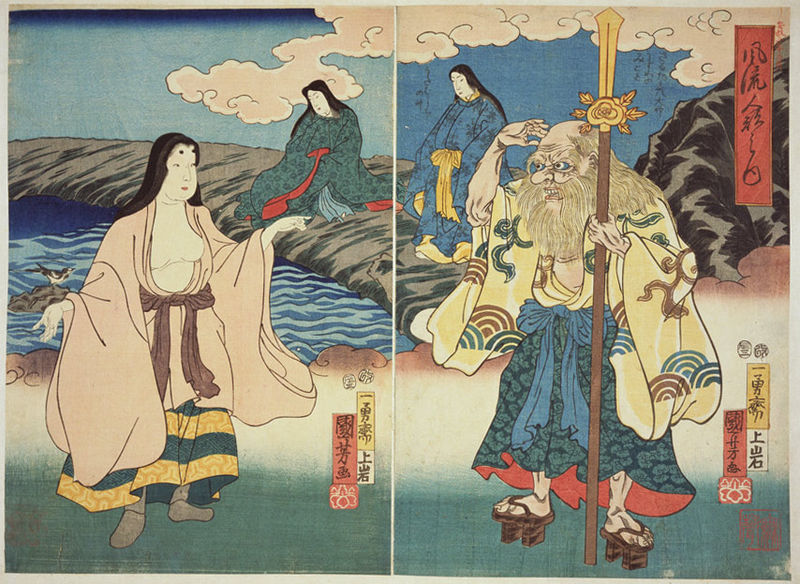

Izanagi Okami and Izanami Okami

Next, the following myths are famous ones, wherein a “female-presenting nipple” (a pair of them) in fact saved the world, twice.

In the first myth, in summary, the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami had hidden in the cave Ama no Iwato due to immense grief. Because of her isolation and neglect of her responsibilities – providing sunlight and management of Earth’s cycles – the world began to spiral into decay and chaos. The other kami came together to come up with a plan to entice her out. Prayers were chanted, divinations were done, beautiful treasures were offered, but nothing worked until Ame no Uzume no Mikoto, a goddess of the dawn, dance, femininity, womanhood, and more, danced and danced.

The atmosphere remained gloomy, but Ame no Uzume no Mikoto remained cheerful, and eventually, exposed her breasts freely. Because she unashamedly, happily exposed her breasts for all of the kami to see, they burst out in joy and even laughter at seeing Ame no Uzume no Mikoto’s ecstasy and freedom amidst the gloomy atmosphere. It was because of the joy, happiness, and pleasure the exposure of her breasts brought, that Amaterasu Omikami finally peeked out of the cave, which led to her being pulled out and restoring light to the world. All thanks to Ame no Uzume no Mikoto’s breasts, and, “female-presenting nipples”

Hardly something to consider shameful, bad, or wrong. In fact, if she had kept them hidden, according to the myth, we may not have the Earth as we know it today, or even survived at all.

The second myth is when, in summary, the Heavenly kami (Amatsukami) were going down to the Earthly realm to rule. In some myths, Sarutahiko Okami came out to greet them, and then married Ame no Uzume no Mikoto upon seeing her beauty, thus joining the Heavenly kami and Earhtly kami (Kunitsukami) as one clan of kami. However, there is another, more critical version of the myth. Where Sarutahiko Okami came to stop the Amatsukami from coming to Earth. No other Amatsukami could defeat him, and they were stuck on what to do in their desire to come toward the Earth. So, they began to consider a war against the Kunitsukami. That is, until Ame no Uzume no Mikoto again took the stage, and approached Sarutahiko Okami by herself, and bravely, unashamedly…exposed her breasts to him.

Needless to say, all thoughts of war dropped from anyone’s head, and the only thought left for Sarutahiko Okami was to ask Ame no Uzume no Mikoto to be his wife, to which she happily accepted, and united the Amatsukami and Kunitsukami kami. In this sense, she saved the world once again, from a world-breaking war between the Amatsukami and Kunitsukami, instead, uniting them.

In this sense, the form of breasts are what once again, restored balance, and protected all life. Ame no Uzume no Mikoto freely showing the beautiful natural form of her naked body is what brought these blessings of joy, life, protection, restoration, happiness, and peace. I feel like we should learn from her and these myths, that when we feel comfortable and confident, and not ashamed of our natural selves, there can be much more happiness spread.

Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and Sarutahiko Okami

Of course, not ignoring the modern sensibilities, I understand the importance of modesty in the general sense of being in public – however when there is the double standard of shirtless “male-presenting nipples” being fine, but shirtless (non-erotic) images of “female-presenting nipples” are somehow seen as taboo or inherently wrong to be banned or even illegal in some cases, this should be re-examined.

Especially when one considers breastfeeding, and a non-erotic context as a general whole. Tumblr’s rule of “no female-presenting nipples” was one of the most ridiculous sentences I’ve ever read in my life. What makes a “female-presenting” nipple wrong and banned, but a “male-presenting” nipple alright? Why is a natural feature of a nude body with extra fat tissue to be banned, but one without isn’t? I know the reason, of course, I know society’s general viewpoint. However what I am saying is – we should sincerely reconsider this, and re-examine our values and beliefs on this particular matter strongly, as this sense of shame and restriction can be very harmful and feed into a larger problem of an unhealthy and skewed view toward sexuality, nudity, and eroticism.

In relation to Ame no Uzume no Mikoto, in the ancient era, miko (female shamans), who Ame no Uzume no Mikoto is the protective goddess of, used to practice sacred sex work in the ancient era. There were even intimate rituals between a miko and her kami. Miko never needed to be virgins, and while even in the modern era the sexual practices of miko are no longer, and the role is only one of a shrine attendant and offering sacred dance to kami, they still do not need to be virgins. The concept of virginity has no real significance or even importance in Shinto.

The next example that is quite famous in Shinto is Kanamara Matsuri. The matsuri (festival) has a big reputation overseas for it’s images of large penises, penis shaped candy, and imagery everywhere. Many foreigners believe this to be a part of the “weird, perverted, wacky” side of Japan – but it’s not. All matsuri are inherently fun and joyful – it’s a festival after all! But there is a very real sincerity behind it. This festival is to pray and celebrate fertility, life, sexual health, and the prevention and curing of STI’s. It’s not just a “wacky penis festival” but something very important for both sexual health and reproduction for couples, as well as general sex between consenting adults and safe practices. In addition, the shrine that hosts the festival, Kanayama Shrine, was famous in the past as frequented by sex workers to protect against STI’s in their field of work, and that carries on into the modern day too. Kanamara Matsuri isn’t the only festival to feature penis imagery, and usually the ones that do always have the same themes: fertility, sexual health, sexual virility, safety, curing and protection of STI’s and so forth. There are other shrines with similar themes too, for example, some Inari shrines in Kyoto with similar imagery, and are also prayed to by sex workers for their protection and healing of STI’s.

Kanamara Matsuri parade

source

In the same manner as the above, in my tradition, Konkokyo Shinto, sex workers pray to Tenchi Kane no Kami-sama for protection and healing, and sex is not viewed negatively. There are many sex-positive teachings, and how nature and even faith itself reflects it. For example, how the sky is viewed like a father kami and the earth is like a mother kami, where the rain that falls from the sky fertilizes the earth to create life – implying in the same imagery as with humans. And that to practice faith single-heartedly evokes the same feeling as when one has sex with their partner, especially if they want to conceive. They are totally focused in the moment, and don’t think of anything else but single-heartedness and love to their partner. I also know of priests who used to be sex workers, and of course many if not the majority of priests and priestesses are sex-positive, and are married with children of their own.

the sky and the earth

Source

Unfortunately, this beauty of Shinto and it’s healthy relationship with nudity, sexuality and sex positivity as a natural and beautiful thing is covered with a dark cloud from modern Japanese society, beginning with the Meiji reformations in 1868 and getting worse over time. Sex as a shameful, hidden, taboo thing has trickled and spread deep into the mainstream society here.

In pre-Meiji era, nudity, sexuality, and eroticism were much more open. Shunga art is the most popular example of this pre-Meiji era openness, and some of this is still seen today in the cases of onsen, or hot springs, where one bathes naked in a public sphere with strangers. However, the positive and healthy views were unfortunately lost. In particular, a whole esteemed and open culture of sex workers was completely destroyed by the Meiji reformation. What was once a highly respected, legal, safe line of work, with a whole esteemed culture surrounding it, was completely decimated. Oiran, who were entertainers of the arts and sex workers, and yuujo, who focused on sex work, were held in high regard. An especially respected and professional oiran or yuujo were named as “tayuu”, a rank which means “best in their art” and were treated very well.

Unfortunately, all that had gone away, and it is now very dangerous for sex workers in Japan, with a lot of challenges. Especially for Japanese professionals in community-based fields, such as being a priestess like myself, society as a whole views any mention of openness about sex or sexual relations, especially in the context of work, as extremely negative and even something to be publicly shamed about.

One doesn’t need to look any further than common news of celebrities or public figures sex life being exposed as a scandal, as if it’s something they should never be let known. It is even more dangerous for sex workers, especially since the anti-prostitution law from 1956. Horrifically, the law states that being a sex worker is a crime, but those who seek their services are not committing a crime. There are loopholes and ways for sex workers to work relatively safely, such as working in an intimacy job that does not promise intercourse, but eventually can lead to it. Thereby being legal by receiving payment for intimacy; whereas receiving payment for intercourse itself would be illegal.

However, while there are ways around it, it’s still a hostile environment, with workers having to not stay at once place for too long. In addition, much more so as Japanese society is very much about saving face and having an external image, knowledge one is a sex worker can make them the target of extreme bullying, harassment, violence, and losing their non sex work source of livelihood /line of work, despite there being many consumers of erotic content and even gravure books openly on shelves in convenience stores. It is quite cruel and hypocritical.

If, for example, I chose to be a sex worker and a priestess at the same time, I would have to keep it completely hidden and private due to the stigma in Japanese society. While there would be absolutely no issue in Konkokyo Shinto as a shrine tradition if I was open about being a sex worker at the same time as being a priestess; there would be a massive issue from the viewpoint of society as a whole, with hostility, mistrust, harassment, and even threats against me and even the shrine itself – in some cases even on grounds of being threatening or dangerous to children, minors, and families who visit the shrine. It is really a difficult and upsetting situation. Not even only for my line of work, but often the same with teachers and educators and any line of work that would involve interaction with families and minors.

I can only wish that Japan returns to it’s roots and view of nudity, sexuality, and eroticism in alignment with Shinto. That it is not seen as something wrong, bad, or dirty – but something to be celebrated, to be honored, to be prayed to the kami for assistance with – and most of all, something normal. Something a part of life. Acknowledgment that without it, we would not be here.

And, most of all, I hope Shinto can teach this around the world. That we don’t need to view these topics in such a negative light. That it can be open, it can be healthy and moderated, and explored in a positive way. This recent decision of social media sites sets us back that much further. And feeds into that negative stigma which harms so many. But I think it’s important to keep pushing back, to educate, and to remove stigma.